Melancthon Taylor Woolsey (1782-1838)

This incredible letter was written by 25 year-old Melancthon Taylor Woolsey (1782-1838) who was born near Plattsburg, New York—the son of Gen. Melancthon Lloyd Woolsey (1758-1819) and Alida Livingston (1758-1843). After studying law for a time, he entered the Navy as a Midshipman on 9 April 1800. His first assignment was the frigate Adams in which he made a cruise to the West Indies in 1800 and 1801. He served briefly in the Tripolitan War just before its end in 1805. In 1807, newly promoted Lieutenant Woolsey received orders to return to the United States aboard the U.S. Frigate Constitution where he was put to work developing a code of signals for the Navy at Washington D. C.

Woolsey was later a hero in the War of 1812 and went on to an honorable career in the US Navy.

In this lengthy letter, written to his father, Woolsey chronicles in great detail his land excursion to the top of Mt. Etna on the island of Sicily just before returning to the United States from the Mediterranean. We learn from the letter he was joined in the excursion by Doctor John Ridgely, an assistant surgeon who had traveled to the Mediterranean on board the the USS Philadelphia but was captured when she foundered in October 1803 and was held captive until June 1805. Just prior to returning to the United States, Ridgely served as US Charge d’Affaires at Tripoli.

There are frequent references to the writing of Patrick Brydone who visited Sicily in 1770 and wrote reverently of Mount Etna. Clearly Woolsey had familiarized himself with Brydone’s work prior to making the trek up the mountain.

TRANSCRIPTION

On board the U.S. Frigate Constitution at Sea

August 25th 1807

My dear Father,

I now begin a letter the receipt of which will announce to you my arrival in the United States. We left Malaga yesterday for Gibraltar where we will take in our stock of provisions and water and probably sail immediately for home.

I have not written you since the first of May last [but] be assured, my dear Father, that want of opportunity alone has been the cause of this long silence. It might, however, be necessary to give you a relish for my letters. Indeed, when I look at the list in my log book and calculate on a successful conveyance of only part of my letters, I cannot but think you must have had a surfeit of them.

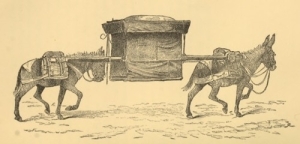

Latigo, or mule litter

On the 19th of May the Hornet arrived at Syracuse from Tripoli and in her Doct. [John] Ridgely, late surgeon of the Philadelphia and who since the release of the prisoners of that ship has acted as American Charge D’Affairs at that Regency. He intended going home with us but when we were at Leghorn last, he could not let slip the opportunity of landing there to make the tour of Italy. On the 23rd of May, I obtained leave at once for a few days to accompany Doct. Ridgely to Mt. Etna. On the morning following, I joined my fellow traveler on shore before sunrise. After a hearty breakfast, we were mounted in our Latigo [see mule litter]—this is a curious vehicle calculated for the extreme rough roads of Sicily. It is only large enough to contain two persons vis a vis and is born by two mules on shafts like a sedan chair. We had two men to take care of the mules, one of them alternately riding the leading horse and driving and driving the hindmost one with a long stick. My servant followed behind on horseback. Thus equipped we set out with our little caravan anticipating some fatigue but more than equivalent pleasure. The morning was extremely fine which with the novel way of traveling (at least to us) more than compensated for the ruggedness of the roads & the apparent danger we often encountered in passing them. It has often been remarked that a sailor tho’ he can with the greatest composure hang suspended by a single rope at a ship mast head in a tempest, yet cannot without his blood’s freezing look down a precipice. I experienced the truth of this remark in the sequel on the road when the path happened to turn abruptly round a corner of the most inconsiderable gulf, our latigo of course hanging over it. I was always in dread less the shafts or some other part of the gear might give way and throw us headlong down.

About 9 o’clock we passed Augusta leaving it about four miles on our right. This town is most pleasantly situated built on an island—formerly an isthmus—that forms the northwestern extremity of the Bay of the same name. It was formerly a place of some note but like all other cities of the Island—Palermo & Catania excepted—are going rapidly to decay. Its number of inhabitants does not at present, I should suppose, exceed ten thousand. About noon we arrived at the top of a small mountain immediately at the foot of which the Plain of Catania begins and here our multeers desired us to alight—the descent being rather dangerous in the Latigo. From this height we had a full view of the whole plain of Catania groaning under the weight of its fruits terminated by the venerable Etna whose hoary head appeared just peeping above clouds which enveloped a part of his upper regions. The beauty of this prospect added not a little to our already high anticipations. Immediately at the foot of the hill there is a hamlet consisting of two or three dwelling houses, a chapel, & a large granary or barn & here we first broached our provision pannies [?] The Hamlet affording us nothing but a small table to eat off of, a couple of brown earthen trenchers & a tumbler. While we were dining, the poor peasants among whom were two or three buxom daughters of Ceres crowded round the door and were extremely officious in assisting the Excellenzas to water &c. Had it not been owing to the smallness of our table, we would have asked them to regale with us; we however made up for this breach of politeness or rather humanity by leaving our whole stock of provisions (except one bottle of port) on the table & I’ll answer for it the poor devils never in their lives before made such a meal of solids notwithstanding they inhabit a land flowing with milk & honey. You must know my dear Father that the little Tlybla [?] is but a few miles from this place. I have tasted of its honey but do not think it any way to be compared with that which is produced in the Island of Minorca or which is made from the honey dew in America.

About two o’clock we were again on our march. We had now quite a different road to travel on, there not being even the most trifling hillock betwixt us & Catania. In our way, we passed through many of the richest wheat fields I ever saw and in many of them the reapers were already at work. We arrived about sunset at Catania and put up at the Elephant Hotel, called so from its fronting the square ____igatha in the middle of which is a fountain and an immense lava statue representing that animal with an obelisk of Egyptian granite on its back. This square is the resort of all the beau monde of the city every in their carriages. We had a letter of introduction to Cavalier Landolina—one of the Knights of Malta—from his nephew Cavalier Landolina & one of our very good friends of Syracuse. We were too much fatigued to dress and deliver it in person and therefore sent it with our address. In the meantime we strolled about a little incognito.

The “Square of the Elephant, Catania, Sicily,” engraved by J. B. Allen after a picture by W. L. Leitch, about 1840.

The first thing we visited was the Cathedral of St. Agatha. The building is very magnificent but remakable for nothing peculiar to itself except its being the repository of the sacred veil of St. Agatha. Among the paintings that adorn its inside we were shown a large birds-eye view of the great eruption of 1669. It is roughly painted but it is said is a very correct representation. It certainly conveys an awful idea of that astounding convulsion.

In the evening Cavalier Landolina called on us at our lodgings. We found him a very polite, communicative old gentleman. After a few minutes conversation, we began the plan of our expedition and before supper was over, it was completely formed. We were to discharge our Latigo, leave my servant at Catania to take care of our baggage, and keep possession of our room and the Doctor, a guide, & myself to set out by daylight for the top of the mountain on mule back. According to this plan, we mounted our beasts before sunrise, the guide carrying on his plenty of provisions, wine &c. We found that our good friend Landolina had sent us a letter of introduction to the family of Sig’r Gemelare at Nicoloni [Nicolosi?] (about 12 miles up the mountain) who he said the evening before were amatures of the mountain.

The morning was very clear and fine but the summit of the mountain was a little obscured which made us fear it would continue so the next day. It was near noon before we arrived at Nicolonia—a small village at the upper edge of the La Region Culta or fertile region & twelve miles from Catania). Our road lay over the roughest country I ever saw. In fact, the greater part of the way you are obliged to crawl step by step over fields of lava still in its roughest state.

In our way up the mountain we had frequent opportunities of observing the wide difference between the inhabitants of this region (particularly about half way up it) and those in the low parts of the island where they are extremely indolent & filthy in their persons and generally of a sallow complexion. But the inhabitants of the mountain—particularly the women—are a fairer complexion, dress plain and neat, and are the most industrious people in the world. We frequently met them carrying large bundles of linen (of which the middle part of the fertile region produces in abundance) on their heads, over this rough road, barefoot & at the same time knitting stockings &c. We met with a very polite reception from the family of Sgn’r Gemielarno. His two sons young men of superior self-acquired educations were extremely attentive.

After a short rest (our anxiety to see all not permitting us to remain long in our place), we set out accompanied by the younger brother to visit Mont Rose—so called from its red appearance. [Paper torn] from this mountain that the great eruption of 1669 issued and laid waste all the country between it & Catania, destroying a part of that city. It is an exact conical figure. Its base I should suppose about four miles in circumference & its perpendicular height not more than eight or nine hundred feet. Its sides are covered with small cinders and ashes which giving way under foot at every step rendered our ascent extremely difficult and tiresome. However, after stopping five or six times to take breath, we at length reached the summit from whence there is a prospect that a thousand times repaid us for the fatigue we had undergone in this essay of mounting & I do not know whether it was the exercise, the change of air (not much cooler but far more salubrious), or my raptures at wonders with which we were surrounded, that had removed in a great measure a distressing sciatic in my right hip with which I had been almost a cripple since the severe gale of wind we experienced in the Gulf of Tunis in the month of March last.

The Crater on Mont Rose was [paper torn] to descend without some danger & more fatigue. We computed its circumference at about three-fourths of a mile. About a mile below this mountain lies the beautiful little mountain of which was once a volcano. It is of the exact semi spherical figure and its crater the same shape inverted. It is covered both inside and out with grass of the richest verdure interspersed with the bleak fields of lava by which it is surrounded. The immense torrent of lava that issued from Mont Rose and swept everything before it in its way to the sea bore with all its force against this delightful little mountain. The prospect is so fine from the top of Mont Rose that two of my brother officers and a midshipman not long since returned to Catania after having visited it imagining that the great crater of Etna could not so far surpass it as to recompense for the trouble and fatigue necessary to encounter in going there.

Next to Mont Rose we visited the Grotto de Colomba or Pigeon Cave. It receives its name from harboring a great many birds of that species. This grotto or cave appears to have been the crater of a very ancient volcano covered nearly to its summit by lavas that have probably been vomited from volcanoes which lie higher up the mountains. At the bottom of the grotto (which is not very difficult of descent) there is a cavern of about 15 feet diameter from whence it is said there sometimes issues tremendous blasts of cold air. It is also said that people have paid dearly for their temerity in descending down this cavern for supposing that they saw infernal spirits they have lost their senses. SR. Gemelaro, however, did not know a single instance of the kind & as for myself, I am disposed to give very little credit to it.

After returning to Nicoloni & taking a heart dinner, we set out on our journey upwards accompanied by the oldest son of Sr. Gemelaro. We were now six in number. Doct. Ridgely was mounted on a large cork pannier containing two large flasks of wine. Young Gemelaro had on his mule two kegs of water. Our Catania guide carried the provisions & spirits, & I sat on a large sack of coats. We had besides a guide well acquainted with the top of the mountain (in the service of Gemelaro who carried firework, a hatchet to cut wood, & walking sticks, & our muleteer (who we dubbed Cyclops, not for his knowledge of the mountain but for his having but one eye) brought up the rear with a long stick to spur on the mules.

We went about a mile out of our way in order to see the Convent of St. Nicola which lies about a mile & a half above Nicoloni. It is a neat building with a long avenue of pines before it. Unfortunately we had not time to pay our respects to the Holy Father who there mortify the flesh with whatever the upper part of the Region Culture affords. After about two hours traveling over scorching fields of lava and cinders, we entered the borders of the woody region, or Region Silvosa, and here we alighted under the shade of a large oak to refresh ourselves with the cool & fragrant breezes with which this delightful region is impregnated, and to wash down the dust we had inhaled on our way with a little Nicoloni wine, which by the by (tho not know in Catania) I think the finest flavored of any I ever drank. Before we mounted again, I put a thick cloth on over my summer jacket.

As we ascended the woody region, a change of climate was percepted at almost every step. At the lower part of it we found the large oaks (with which this Region is thickly wooded) in full foliage and the leaves less forward as we ascended until we arrived at the upper part of it, where the buds were just making their appearance. We found the road much better in the woody region than that we had already passed for instead of crawling step by step over rough beds of lava & in the scorching sun at the risk of our necks, we were now traveling under the grateful shade of spreading oaks on a rich soil covered with herbage interspersed with a variety of beautiful flowers. We had an opportunity of discovering the depth of the upper stratum of earth in this region—in many places our road lying immediately along the banks of torrents whose beds of the most ancient lavas were in some places not less than perhaps thirty or forty feet below the surface of the soil. What an idea does this convey of the great antiquity of the mountain—especially when we reflect that an age is hardly sufficient to form a strata of earth capable of producing the smallest vegetation.

It is now 138 years since the great eruption of Monterose and in the whole course of that destructive torrent there is not the least appearance of a shrub or even a blade of grass, the garden of the Benedictines of Catania excepted, & I believe the earth that covers the rock of lava in that is brought from some other place. It was not in my power to procure the natural history of the mountain of Catania. Young Gemelano, however, informed us that the woody region abounded in porcupines, hedgehogs, wild boar, and that on the north side of the mountain there are a few deer but that the breed of the latter are nearly extinct. Of the feathered race, he says there is a great variety some of which have the most melodious notes. We had the misfortune to see none but a little bird resembling very much the canary, one raven, & heard the melancholy note of cuckoo at a distance.

About an hour after sunset we arrived at the Casad neve or snow house where we put up for the night. It is a very little stone or rather lava house about six miles up the Region Silvosa built by the Prince of Paterno (to whom the whole of the deserted region belongs) for the accommodation of the snow carrier. It was our intention when we left Nicoloni to have above the Philosopher’s Tower where the young Gemelaro’s truly amatures of the mountain have erected a small house large enough for the accommodation of eight or ten persons, but before we reached the snow house who they had sent the day before to see if their house was in order he informed us that it was blown full of snow and that the door could not be got open. This was no small disappointment as we began to anticipate a great deal of pleasure lying round a warm coal fire all night.

After securing our mules to the trees, we went to see the Spelonia Capriole or goats grotto of Mr. Brydone, now the Spelonia del Inglise or English Grotto. Perhaps the original name was changed from his having slept there. We found nothing more ruinous in it than any other shelving rock which could shelter twenty or thirty goats. For a great distance round both this cave & the Casa de neve, the bark of the oaks is peeled off & the names of the many persons whose interest or curiosity has brought them high cut on the bare wood. Ridgely & myself followed the example.

The snow house stands on the brink of a pretty steep hill from whence there is truly a sublime prospect. The City of Catania, the town of Nicoloni, and the many villages and delightful villas between them, Monte Rose with the whole course of its lava bordered by beautiful orchards, gardens & wheat fields appear almost at your feet. Casting the eye a little further you behold the east and south coasts of Sicily with all their indentures. Even the harbors of Syracuse & Augusta were plainly to be seen & we thought we could see the Temple of Minerva in Syracuse. We sat on the ground before our door with our eyes riveted on the enchanting scene until after sunset.

When Ridgely went to visit a neighboring lava, young Gemelaro began to cut wood for our night’s fire, I to gather dry oak leaves for our bed in baskets we found in the house, probably left there for that purpose, & our guides hearing the bleating of goats a little way down the mountain to the westward had already gone in search of milk. About dark they returned without having been able to get us any. We built a large fire in the middle of the house round which, seated on our saddles, & panniers, we made a comfortable [paper torn]. You may be assured after such a days work we did justice to the deviled fowls and broiled mutton &c. we cooked ourselves on the coals. After supper, wrapping ourselves up in our great coats, we laid down on our bed of leaves, keeping the poor cyclops adding fuel and stirring the fire. A little boy a mile or two off having heard from our guides that there were two Excellenza’s at the Casade neve who had sent them in search of milk, brought us a large kettle full of it about nine o’clock. Ridgely & myself got up, took each a hearty drink of punch, put the remainder in our empty wine flasks, paid the little boy well for his trouble, and went to bed again.

A little before midnight, imagining that we had overslept ourselves and fearful of not arriving time enough at the top of the mountain to see the sunrise, we saddled our mules and after muffling ourselves up in great coats & handkerchiefs about our ears and taking each a hearty drink of raw brandy, we began again to ascend. The night was perfectly clear and the air piercing cold. To our no small regret we had no philosophical instruments with us. After traveling at a very slow rate for upwards of an hour, we arrived at the boarders of the Region Scoperta—or deserted region—where the road began to be more rugged & difficult of ascent. Our beasts, fortunately, were very sure-footed for we left it entirely to them to choose their way along the edges of some precipices which at that hour appeared deep & gloomy. We had not proceeded far in this region when we heard a number of voices behind us. We knew we were far above the inhabited part of the mountain and consequently began to be under some apprehension that a Banditi had dogged us from the regions below. Ridgely & myself felt ourselves in a very awkward situation as Sign’r Gemalaro who said the sulfurous smoke at the top of the mountain would tarnish the guilt on our swords [and] had advised us to leave them with him until our return. The poor people below were under the same apprehensions for us & sent one of their guides to see who we were when we learned that they were four English Sergeants of the troops stationed at Catania. We shortly after joined company and traveled on together sometimes riding, at others walking, both to relieve our poor beasts & keep our feet warm.

Our road became now pretty steep but not near so difficult of ascent as Mr. Brydone describes it. The large fields of moss we crossed afforded an excellent footing. About two o’clock we arrived at the house of the young Gemalaro’s which is about two miles from the very summit of Etna. Here we alighted & with the coals we had brought with us made a fine fire round which we drank the remainder of our milk punch, probably the first ever drank st the same elevation above the surface of the earth. We had now three or four hours wait to see the sunrise which was the object of our early departure from the Casa de neve. After resting ourselves a few minutes, we ran out to the edge of the plain on which we were to collect of possible something of a night prospect at this elevation; but altho the sky was perfectly serene, our sight could not penetrate the profound darkness in which the great world at our feet was enveloped, and the ground on which we stood appeared like a stage floating in an immense void independent of it. The cold was too intense for a long contemplation of this sublime prospect of nothing. We therefore returned to our fire and seating ourselves in the ground around it, waiting impatiently for returning day, all the time imagining that it was far from here Mr. Brydone saw the sunrise. In the meantime, our attention was wholly taken up with the great crater above us, every now and then discharging vast columns of smoke & ashes, which ascending to an immense height would float gradually with the wind, the heavy particles falling on us like a drizzling rain.

At length the dawn appeared when we again took our lookout post and now, my dear Father, I have come to the part of my narration of which for me to undertake giving you a description dressed off in its proper colors would be truly attempting the chariot of the sun. Indeed it would be a task for the inspired pen of the immortal Milton. Mr. Brydone’s description, as far as I am capable of judging, I think elegant and altho he modestly apologizes for want of language to describe fully the sublimity of the prospect or its affects on his imagination, yet no one after seeing the sunrise from the top of Etna will attribute his apology to an excess of modesty. I give it to you in his words—-

“But here description must ever fall short, for no imagination has dared to form an idea of so glorious & magnificent a scene [paper torn] is there in the surface of this globe: any on point that unites so many awful & sublime objects, The immense elevation from the surface of the drawn as it were to a single point without any neighboring mountain for the senses and imagination to rest upon; and recover from their astonishment in their way down to the world. This point or pinnacle raised on the brink of a bottomless gulf, as old as the world, after discharging rivers of fire, and throwing and burning rocks with a noise that shakes the whole island. Add to this the unbounded extent of the prospect, comprehending the greatest variety and the most beautiful scenery in nature; with the rising sun advancing in the east to illuminate the wondrous scene. The whole atmosphere by degrees kindled up and shewing dimly & faintly the boundless prospect around. Both sea & land looked darkly confused as if only emerging from their original chaos; and light and darkness seemed still undivided, till the morning by [paper torn] advancing, completed the separation. The stars are extinguished and the shades disappear. The forests which but now appeared black and bottomless gulfs from which no ray was reflected to shew their form or colors, appeared a new creation rising to the sight, catching life and beauty from every increasing beam. The scene still enlarges and the horizon seems to widen and expand itself on all sides; till the sun like the great Creator, appears ion the east and with his plastick ray completes the mighty scene. All appears enchantment & it is with difficulty we can believe we are still on earth. The senses unaccustomed to the sublimity of such a scene are bewildered and confounded; and it is not till after some time that they are capable of separating and judging of the objects that compose it.”

After feasting our eyes on this magnificent prospect till nearly half an hour after sunrise, we set out for the cone of the crater now called as the whole mountain formerly was Mongibello which is derived from Gibel el nan or mountain of fire—the name given to it by by the Saracens when they had possession of the island. After crossing a bed of very rough lava we had good footing on the snow until we nearly reached Solfaterra about one quarter the way up. This is a most curious place. There are a great number of fissures in the snow fifty yards in length and not more than three or four feet wide from whence there is a thick cloud of smoke a little impregnated with sulphur constantly issuing. The ice in many places has formed I cannot tell how over these to the thickness of many feet, the under part of which constantly thawing by the warm vapor from the chasms leaves an extensive arch from which the great icicles are abundant, that from from above look like so many crystal columns. In some places where the holes are smaller, the vapor more confined and consequently hotter, it has thawed quite through & in the middle of the field of snow you see a large column of smoke rising up. The whole of the sides of Mongibello are covered with immense round rocks & stones thrown from the crater. Some of these by uniting all our strength we sat in motion when they rolled down to the bottom of the cave with most tremendous crashing.

After resting at almost every ten steps, we at length reached the brink of the crater on the south side. If there is a place or situation in this world that can at the same time make man feel his littleness or elevate him above his nature, it is here. On one side he sees the whole world enriched as it were by all the beautiful hand of its creator with unclouded seas, scattered islands, rich plains, rugged mountains, smooth lakes, meandering streams, thick forests, and in fact, all the climates with all their rich variety laid as it were at his feet. He feels himself God, casting his eyes. On the other side his head swims at looking down a bottomless gulf raging with eternal fires and sometimes vomiting ruins of liquid flame overwhelming in its course poor feeble man with all his vain possessions. At the same time reflecting that the slightest excavation would tumble him headlong down this dreadful abyss, he blushes at his own insignificance.

At first we laid down, just peeping over the edge of the crater—not daring to trust our feet as a fall either way appeared equally fatal. Ridgely at length, summoning resolution, stood up and putting one foot over the brink said that at least he had one foot in the crater. The moment I saw him, shuddering at his perilous situation, I involuntarily caught him by the coat and dragged him with force on the ground by me, at the same time reminding him of the fate of the Philosopher Empedocles who you know it is said threw himself in the crater that the world might believe he was taken up to Heaven. I think this a very improbable story & am more willing to believe that speculation led him too near the brink from whence he accidentally tumbled in. After becoming a little more reconciled to a sight which at first gave us all the vertigo, we ventured to crawl round the crater to the west side from when we saw apparently at no great distance all the north coast of Sicily, all the Sipari islands, the fare [?] of Messina, all Calabria, and the coast of Italy to a great extent & directly at the foot of the mountain on this side stands the little towns of Bronte & Paterno—the latter surrounded by lava. We could neither see Messina or Paterno; the high mountains at the back of them intervening. We could not see the Adriatic Sea beyond the mountains of Calabria. Mr. Brydone of course fibbed a little when he said he saw the sunrise [paper torn] the sea for he visited the mountain at the same time of the year we did, when the sun had of course nearly the same declination. I very much doubted whether it was seen to rise clear of St. Maria which forms the Northeastern boundary of the Gulf of Toronto even in the winter solstice.

The great crater, I imagine, is not less than between two miles and a half and three miles in circumference The south and east sides are perpendicular or rather hang over the great mouth of the crater or chimney of Etna which cannot be less than fifty yards in diameter. The west and north sides go shelving down to the crater round the foot of a small volcanic mountain formed by a recent though very inconsiderable eruption. This mountain whose head is just at a level with the brink of the crater at present, only emits sulfurous smoke. Ridgely unfortunately inhaled a little of it and was nearly suffocated. While we were on the brink, there were several great discharges of smoke & ash & our guides said they saw stones. We, however, did not. A minute at least before the smoke made its appearance, we heard a rustling noise underneath us. After the first impression of terror had a little worn off, taking a bottle of liquor in my hand, I discarded about forty down the crater where up to my ankles in ash almost hot enough to burn my boots. I poured out a libation to Vulcan & next to St. Agatha to withhold her wrath against us infidels until we should safely reach Catania. I assure you, my dear parents were not forgotten for I drank a bumper to their health before I ascended to my companions with the bottle. You may be assured they did not follow my example in pouring out libations.

We found some large stones on the south side on our way back again that by a little labor we loosened so that they fell into the mouth of the crater. After they disappeared about five seconds we heard a noise resembling that of a heavy cannon at a great distance & we counted five of the noises doubtless the stone bounding from side to side on its way down to the bottom of the mountain, each one more faint & at a greater distance of time apart. Before we set out on our return down the mountain we seated ourselves on the ground to take a farewell look of the sublime and extensive prospect which presented itself to our view. The first thing that presented itself to us was the Desert region or Frigid Zone where eternal fires & snows have fixed their abode and which is so perfectly sterile as not to afford sustenance to anything that lives, moves, or has a being. This region is immediately succeeded by the woody region or Temperate Zone of about the same extent (eight miles) forming a girdle of the liveliest green quite round the mountain making a very pleasing contrast with the regions in separates. The small conical & spherical mountains occasioned by the many eruptions of Mt. Etna are more numerous & exhibit a greater variety of colors in this than in the other two regions. I think I counted 180 of them in the southern sides sides of the mountain only looking directly in their craters. The fertile region or Torrid Zone came next in view. It extends at least twelve miles from the woody region and is charmingly diversified with everything that population & extreme fertility in the most delightful [paper torn] can render interesting to the beholder. It is bounded by the sea on the east or southeast and by the rivers Aleatana and Semetus which meander beautifully at the foot of the mountains on all the other sides. Casting our eyes a little farther we behold the extreme and fertile plain of Leontini variegated like a rich carpet with different colored fields. Nearly in the middle of it stands the city of Leontini on the bank of the lake.

….described whatever I have seen. The ancient theater, Bath & Rotunda, the place where the lava of 1669 scaled the city walls, the church & convent of the Benedictines. The Prince of Biscani’s museum and theatre & the library of the University &c.

On the evening of the 27th, we hired an open boat rowed by four men to carry us to Syracuse. The stern sheets were covered with a good awning and in the bottom of the boat were beds for us to lay on. About eleven o’clock we set out accompanied with the best wishes of our worthy friend the Cavalier. We arrived at Syracuse about seven o’clock in the morning.

On the 11th of June we sailed for Messina where we did not arrive until the 15th. We staid but three days at Messina. I spent almost the whole of my time with your cousin, Capt. Muerson [?] & feel very much indebted to him for his attentions. He is paymaster of the 81st Regiment of foot and was in the battle in Calabria last summer.

Palermo in the early 19th Century

We sailed from Messina to Palermo where we arrived on the 21st and on the 25th sailed again for Leghorn. During our stay at Palermo I spent what time could be spared from duty in viewing the city and its environs. Palermo is the most populous and best planned city in the island. The two principal streets are at right angle with and intersect each other and intersect exactly in the middle of the town & from the Ottagono, a large square from whence can be seen the lower gates of the city. The small streets in each quarter of the city run parallel generally with the great streets of which they are bounded. The houses of Palermo are mainly of stone which gives the city a heavy appearance. The lower stories as in all the other cities I have seen in this part of Europe are appropriated to stops, stores, stables, &c. The population of Palermo since it has become the residence of the Court, I think is about two hundred thousand. The marina is the most extensive and most pleasantly situated of any I have yet seen in this part of Europe.

…resort of all the gay of the city every evening carriages. We would have rather walked but as we certainly should have rendered ourselves either extremely mean & poor in the eyes of people whose customs would have been broken through. We equipped our servants in a decent livery and putting two behind each carriage paraded the marina every evening during our stay. The roads about Palermo are the best I ever saw, Both to the west & east of the city & along the sea shore there are a number of noblemen’s [illegible] visited those to the eastward at a place called Bagheria about twelve miles from town.

The continuation is under another cover or rather will be for the next conveyance.

— W. T. Woolsey

[Poem, My Native Land]